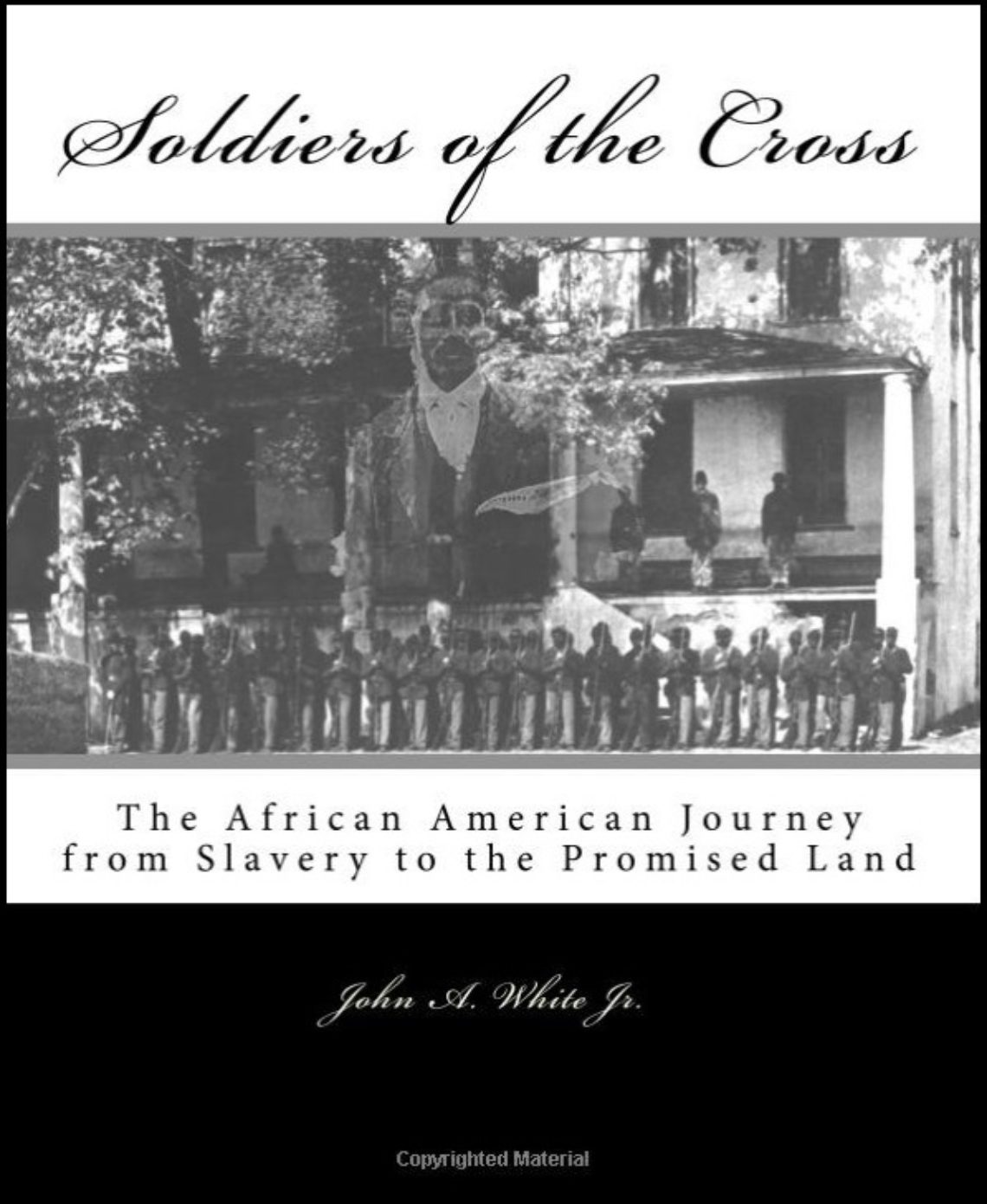

Fig. 34. Black Troops Entering Charleston, Harper’s Weekly, March 18, 1865

South Carolina was the first state to succeed from the Union and the Civil War started in south Carolina at Fort Sumter. The first black regiment was formed in South Carolina as well making the state an important part of Civil War history. On February 18, 1865, black troops fighting in the advance of the Union army were the first to enter Charleston. The Harper’s weekly illustration reads, “Marching on!”–The Fifty-fifth Massachusetts Colored Regiment singing John Brown’s March in the streets of Charleston, February 21, 1865.”

A parade was organized by emancipated blacks of Charleston to celebrate their liberation on March 21, 1865. A report of the parade appeared in the New York Daily Tribune on April 4, 1865 called, “A Jubilee of Freedom”: Freed Slaves March in Charleston, South Carolina.[1]

There was the greatest procession of loyalists in Charleston last Tuesday that the city has witnessed for many a long year. The present generation has never seen its like. For these loyalists were true to the Nation without any qualifications of State rights, reserved sovereignties, or other allegiances; they gloried in the flag, they adored the Nation, they believed with the fullest faith in the ideas which our banner symbols and the country avows its own. It was a procession of colored men, women and children, a celebration of their deliverance from bondage and ostracism; a jubilee of freedom, a hosannah to their deliverers.

The celebration was projected and conducted by colored men. It met on the Citadel green at noon. Upward of ten thousand persons were present, colored men, women and children, and every window and balustrade overlooking the square was crowded with spectators. This immense gathering had been convened in 24 hours, for permission to form the procession was given only on Sunday night, and none of the preliminary arrangements were completed till Monday at noon.

Gen. Hatch, Admiral Dahlgren and Col. Woodruff gave their aid to the movement; and thereby the 21st Regiment of U.S.C.T., a hundred colored marines and a number of national flags gave dignity and added attractions to the procession.

The procession began to move at one o’clock under the charge of a committee and marshalls on horseback, who were decorated with red, white and blue sashes and rosettes.

First came the marshals and their aid[e]s, followed by a band of music; then the 21st Regiment in full form; then the clergymen of the different churches, carrying open Bibles; then an open car, drawn by four white horses, and tastefully adorned with National flags. In this car there were 15 colored ladies dressed in white, to represent the 15 recent Slave States. Each of them had a beautiful bouquet to present to Gen. Saxton after the speech which he was expected to deliver. A long procession of women followed the car. Then followed the children of the Public Schools, or part of them; and there were 1,800 in line, at least. They sang during the entire length of the march:

John Brown’s body lies a moulding in the grave,

John Brown’s body lies a moulding in the grave,

John Brown’s body lies a moulding in the grave,

His soul is marching on!

Glory! Glory! Glory! Hallelujah!

Glory! Glory! Glory! Hallelujah!

We go marching on!

This verse, however, was not nearly so popular as one which it was intended should be omitted, but rapidly supplanted all the others, until at last all along the [ ? ] or more of children, marching two abreast, no other sound could be heard than

We’ll hang Jeff. Davis on a sour apple tree!

We’ll hang Jeff. Davis on a sour apple tree!

We’ll hang Jeff. Davis on a sour apple tree!

As we go marching on!

A similar parade occurred again in Charleston a month later. A Confederate prison for Union soldiers was located in Charleston at the site of the elite Washington Race Course and Jockey Club. The site contained a mass grave of Union soldiers. Because of the “no-quarter” Confederate policyfor captured black soldiers, prisoner exchange was halted and many Union soldiers died in unsupplied confederate prisons. Many of the Union soldier remains were exhumed and given a proper cemetery burial at the site. A parade of 10,000 people was organized to dedicate the Union cemetery, which was the first Memorial Day Celebration.[2] The procession started at 9 am on May 1, 1865. At the head of the procession was three thousand black schoolchildren carrying roses and singing “John Browns Body.” They were followed by several hundred black women carrying flowers and wreaths. The men marched next followed by Union soldiers. At the cemetery the children sang ““We’ll Rally around the Flag,” the “Star-Spangled Banner,” and several spirituals”. Black ministers read from scripture: “for it is the jubilee; it shall be holy unto you… in the year of this jubilee he shall return every man unto his own possession.”

[1] History Matters “A Jubilee of Freedom”: Freed Slaves March in Charleston, South Carolina, March, 1865, http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/6381/

[2] David W. Blight, The First Decoration Day, https://zinnedproject.org/materials/the-first-decoration-day/